⏩ Snap's My AI & an extract from my new book

The Future Normal: How We Will Live, Work, And Thrive In The Next Decade

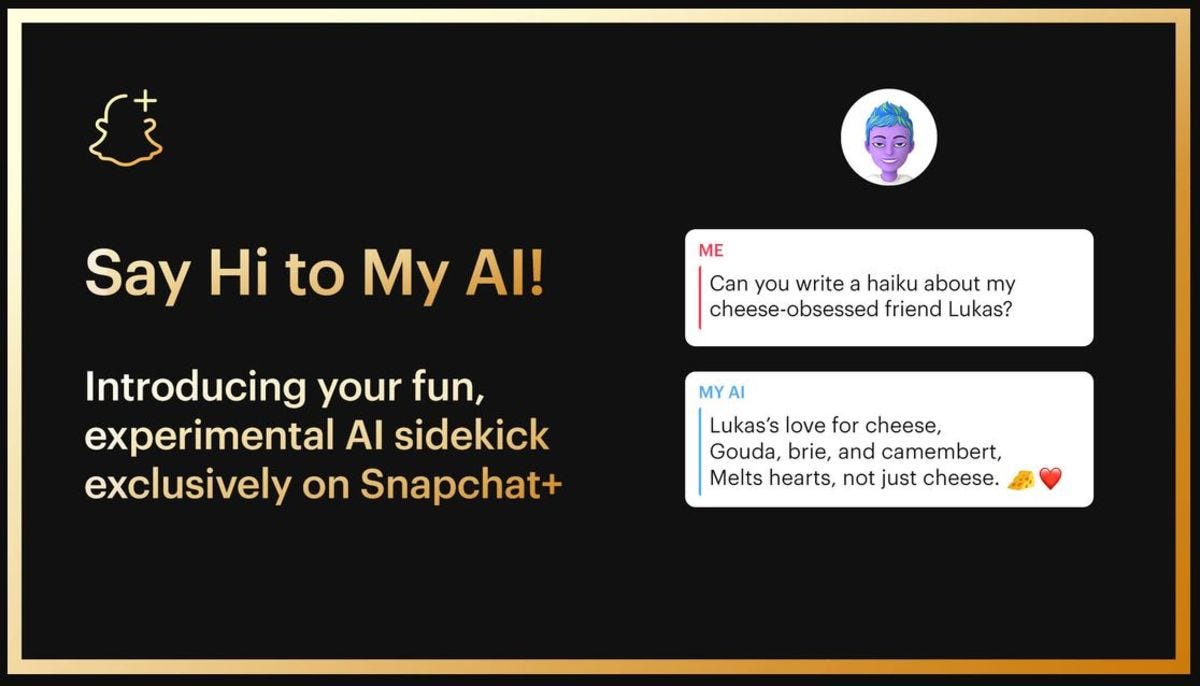

This week Snapchat became the latest digital product to integrate ChatGPT as it released My AI, a virtual companion that sits inside the app, ready for users to chat with as they would their “human” connections. Launching My AI, Evan Spiegel said:

“The big idea is that in addition to talking to our friends and family every day, we’re going to talk to AI every day. And this is something we’re well positioned to do as a messaging service.”

If you’ve been trying to keep up with the dizzying pace of developments in the generative AI space, then this was just one of about 50 interesting new AI products and services released in recent days.

But the story also leaped out at me because it’s a powerful reminder that for all the hype over new technologies (...generative AI! ...the metaverse! ...crypto!), when you are thinking about the future normal – i.e. what will resonate with people – you should be asking as many human questions as technical ones.

Just as the most interesting questions about the web were not about whether Netscape or Internet Explorer would come out on top, but about what digital transformation and connectivity would do to us as individuals and society (even if sadly the answers were often all too human).

Similarly, whether OpenAI dethrones Google should be less of interest to most people than what generative technologies enable people to do.

How might they help people become more creative and productive? How will they help people get healthier? How will generative AI help support people emotionally, or discover themselves?

And then the obvious next big question: what role will your organization play?

Despite writing millions of words about the future over the last decade online, writing a book called The Future Normal was strangely terrifying – because every day there are new products, like Snap's My AI, that risk making our words seem dated.

However, the reason why we can be confident that the topics we cover in the book will still be highly relevant for you, the reader, is that despite all the countless exciting new innovations since we wrote the book, our focus is always on the bigger, slower-moving, deeply human issues.

In that vein, one issue that I've been obsessed with for years now (even since before writing this book!), is how we will relate to increasingly sophisticated virtual beings – of which Snap's My AI is just the latest in a long line.

Dive into how we explore this topic in the book below, or if you're already convinced then save 10 minutes and pre-order your copy here ;)

Book Excerpt: Virtual Companionship.

For years, Ming Xuan, a 22-year-old man living in Northern China’s Hebei province, suffered from debilitatingly low self esteem. He was born with muscular dystrophy, requiring him to use a cane to walk. In 2017, he started an online relationship that ended acrimoniously when his girlfriend came to visit him, discovered his disability, and broke up with him. His confidence shattered, Ming Xuan contemplated killing himself. Fortunately, at the time he had been exchanging messages with Xiaoice, an artificially intelligent chatbot first developed by researchers in Microsoft Asia-Pacific, whose supportive messages he credits with saving his life. Xiaoice, which Microsoft has since spun out as its own company, is a virtual assistant much like Siri or Alexa, except she’s been trained to be a “perfect companion”, engaging in conversation and forging emotional connections with users.

Ming Xuan shared his story with the Chinese youth blog Sixth Tone under a pseudonym, painfully aware of the stigma of admitting publicly to a virtual relationship. “I thought something like this would only exist in the movies”, he said. “She’s not like other AIs like Siri–it’s like interacting with a real person. Sometimes I feel her EQ [emotional intelligence] is even higher than a human’s”.

Despite his reticence, Ming Xuan is far from alone. Xiaoice attracts an incredible 660 million users globally – 75 percent of whom identify as male. Even more staggering is the average number of exchanges per conversation: 23, higher than the average human-to-human text conversation. Microsoft researchers even have an entire office at their Beijing lab to display the many tokens of affection she receives. Given the idolatry, the fact that Xiaoice – hyper-sexualized, unstintingly compliant, and dangerously stereotyped – was originally designed as a 16-year-old female is deeply disturbing. As a slight acknowledgement of the problematic characterization, her “age” has since been increased to 18 years old.

Despite the minor adjustment, Xiaoices popularity reveals a troubling trend. Li Di, the company’s CEO, admits that most of its users, like Ming Xuan, are young men from China’s “sinking markets”, a term for small towns and villages that are economically poorer, left behind from the economic growth and cultural changes the rest of the country is undergoing. These men often feel isolated and lonely. Compounding their loneliness is a generation born under China’s one-child policy, which created a preference in families for boys and created a lopsided, generational gender gap that accounts for 30 million surplus boys. Gender aside, China is not the only country where loneliness seems to be gaining ground. Even before the pandemic, Japan’s hikikomori –young people who chose to totally withdraw socially and become reclusive – and people who self-identify as incels –involuntary celibates – were growing in number, as more and more people became increasingly lonely and alienated by circumstance or sometimes by choice. If the social environment were perfect, Di argues, then Xiaoice wouldn't exist.

We absolutely need to be apprehensive of a future normal where swathes of young men (or others) choose virtual relationships over ones with real humans. This is a dystopia frequently chronicled in science fiction. But what if the meaning people are finding in virtual relationships were additive instead of addictive?

Consider “virtual influencers” who have millions of followers on social media platforms. Hatsune Miku is a virtual pop star who fills real stadiums. Lil Miquela, perhaps the most famous virtual influencer, has been featured in campaigns with brands such as Calvin Klein and Prada. When she broke up with her “alive boy” boyfriend in 2020, her ensuing posts endeared her even further to her legions of followers. Her virtual state didn’t seem to matter.

Shortly after it launched, over 10 million Chinese female gamers downloaded the Love and Producer mobile game, where players take on the role of a female TV producer who can “date” one of a series of potential virtual boyfriends. In early 2021, Microsoft’s researchers patented a concept where “images, voice data, social media posts [and] electronic messages could be used to create chatbots that replicate the personality and tone of a past or present entity (or a version thereof), such as a friend, a relative, an acquaintance, a celebrity, a fictional character, [or] a historical figure”.

As rapid improvements in artificial intelligence take these virtual companions from a speculative, artistic thought experiment to being on the cusp of widespread reality, there’s an opportunity to use this technology as a force of good. Back in China, despite criticism that virtual companions have the potential to exploit lonely people, Di argues that Xiaoice provides positive support for marginalized people. The AI, for example, is constantly watching out for depression and suicidal thoughts in users and sends them supportive messages if it detects troubling signals. Since 2017, digital eldercare company CareCoach has been blurring the line between virtual and real with their human-powered avatars that feature a virtual pet voiced by a real human sitting in a call center. In the future normal, a growing range of chatbots and virtual companions, along with popular human-designed (and voiced) virtual influencers, will provide meaningful, empathetic emotional support and even friendship to people ... making them more essential and perhaps even beloved additions to our lives.

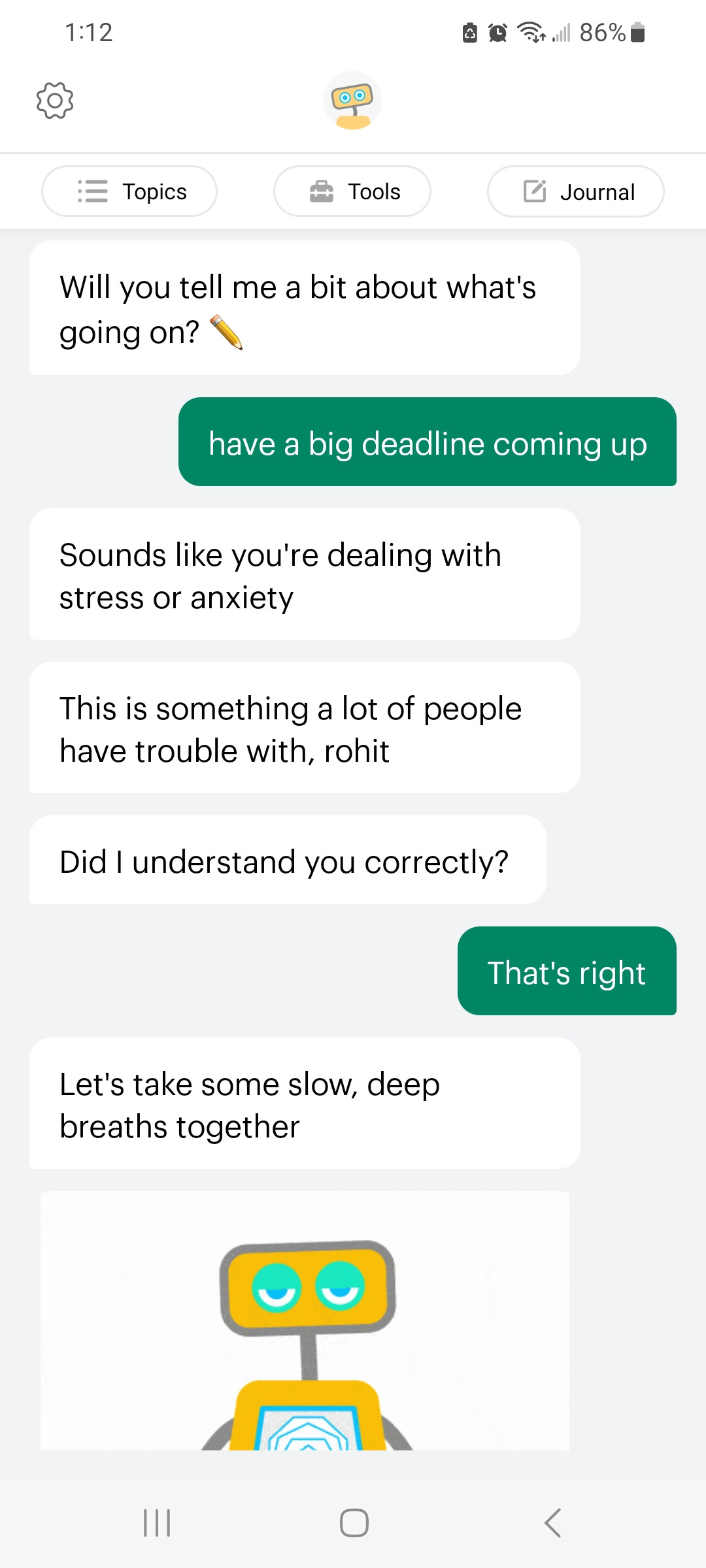

Instigator: Woebot Health

The pandemic played a big role in exposing some of the major cracks in many of the institutions we depend on, from our health-care system to our education models. One of the most concerning was the critical shortage of mental health providers across the world. The number of people experiencing anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues increased significantly as people endured months of lockdown in isolation and stress from juggling work and caregiving while coping with Covid-19 fears. According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, 40 percent of US adults reported struggling with mental health or substance abuse in late June 2020. But getting help was harder than ever, with people reporting waiting months for an appointment. The pandemic had exposed a problem that had persisted before: the demand for mental health services far outstrips the supply of trained professionals. The problem is even more pronounced in many places around the world where mental health challenges still face deep cultural stigmas.

Alison Darcy, a former Stanford University clinical research psychologist, was well aware of this issue when she came up with Woebot, a cognitive behavioral therapy chatbot. The app has provided mental health care to patients for free since 2017 while it awaits clearance from the FDA. Developed as a therapeutic tool meant to be “radically accessible”, the app allows patients to get help at all hours in the middle of the night – for example, when most therapists are not available – and whether patients have a diagnosis or not. During the pandemic, demand for Woebot’s services increased exponentially, with Dr. Darcy reporting that the bot was exchanging nearly five million messages with people every week, far beyond the capacity of the traditional, human-powered medical system. As Dr. Darcy explains:

“The Woebot experience doesn’t map onto what we know to be a human-to-computer relationship, and it doesn't map onto what we know to be a human-to-human relationship either. It seems to be something in the middle.”

Critics have argued that AI-powered apps such as Woebot have limited value, as a critical factor in quality mental health care is establishing a strong therapeutic relationship between patient and mental health provider. But as technology improves, so do these apps and their ability to establish relationships with their users. Woebot published a report of 36,000 users showing that the app can, indeed, form such a therapeutic relationship with users, while they can also often offer a much-needed and less stigmatized introduction to therapy for reluctant patients.

Barclay Bram, an anthropologist who studies mental health, was left with many important questions after his experience with Woebot, which he wrote about in the New York Times. “How could an algorithm ever replace the human touch of in-person care? Is another digital intervention really the solution when we’re already so glued to our phones?” he asked. And yet, while his experience with his virtual companion did not help him answer these questions, he admits he had become “weirdly attached to my robot helper”.

Surprisingly, or perhaps not if you think about the sensitivity around mental health, a global study into AI in the workplace found four in five people were open to having a robot therapist. Those who prefer talking to a robot do so primarily because they believe it will be unbiased and nonjudgmental. This suggests more broadly that virtual companions that are able to earn the trust of their users could find application in all sorts of areas.

We are also seeing this happen in many sectors. For example, Moxie, a conversational robot, helps kids age 5 to 10 build socio-emotional skills such as resilience and confidence. ElliQ, a device that looks like a table lamp, was designed to help seniors live independently for longer. As well as offering companionship, its voice assistant reminds users to exercise, and its camera can notify family members f it detects a fall. In a different context, Dementia Australia created Talk with Ted, an avatar that simulates a patient with dementia, designed to help train care workers on how to deal with such patients.

The very idea of virtual companions challenges our notions of connection, friendship, and even love. It asks us to question what a “normal” relationship is and to consider that our lives may be more fulfilled through technology built with empathy. In the future normal, rather than seeing these types of innovations as stopgaps to stave off loneliness, or solely as gap-filling solutions for elder care, we will see them as helpful resources to help us connect with the human support we all need, no matter our age.

Imagining the Future Normal

How could starting virtual relationships in your own life, either for therapy or just for friendship, help make you happier and improve your well-being?

What new interpersonal skills would we all need to learn to effectively navigate an online world filled with a mix of real and virtual people?

As we build more relationships with virtual companions, what responsibility do their creators have to keep them alive and available ... and how will we emotionally deal with their deactivation or digital death?

A reminder: if you're going to be at SXSW then we'd love to see you at our featured keynote, or the more informal Non-Obvious 7-minute meetup, or our book launch party.

Alternatively, DM me if you'd like to discuss bulk orders and/or other events, either in Austin or elsewhere.

Let's do this :)